Sometimes when investing, the things you don´t do are as important as the things you do.

In finance, noise refers to any information that serves to confuse the investor or misrepresent the underlying market trend. On a mundane level, noise is the day-to-day vicissitudes in asset prices that lead the investor to question where the longer term trend is heading. More seriously, almost all the writings of the financial press are noise aimed at explaining why prices are moving, but which only serve to confuse the investor. As he second guesses his analysis, this new information betrays his rational decisions and leads him to err in exactly the way that hurts his bottom line.

Market noise makes it difficult for the investor to determine what really drives the market and is easily confused with short-term volatility. This is especially true at market bottoms.

Example 1: The cover of the August 13, 1979, edition of BusinessWeek proclaimed “the death of equities.” The S&P 500 closed the month at $109 and was throwing off a healthy 5.6% dividend yield at the time. Of course, year-on-year inflation was nearly 12%. The general economy was trudging along with unemployment at 6%. The outlook was gloomy and BusinessWeek was echoing this general sentiment through its cover.

The BusinessWeek cover came hot on the heels of a major market low in February 1978. In fact, if one tried to find a more severe market bottom he´d be hard-pressed to do better than the magazine’s editors.

Buying the S&P 500 in August 1979 would have yielded the investor 8.9% annually if he held until today. Accounting for dividends accumulated along the way, he would have earned just shy of 12% a year. For a thousand dollar initial investment, the investor´s account would now show almost $100,000.

Of course, to take advantage of this great buying opportunity the investor had to first overcome a herculean hurdle: ignore the news, see through the noise, and listen to what the market was saying.

Example 2: In October 2003 the world was in the midst of the “Peak Oil” panic. The Economist´s cover on October 23 of that month declared “the end of the Oil Age.” It didn´t just surmise that this end could be near but stated it as a foregone conclusion.

West Texas Intermediate crude oil closed that October at $29 a barrel. Again, the time surrounding this dour news was filled with record low prices for the commodity. A major bottom formed less than a year earlier, at the April 2003 low of $25.

By the time oil peaked in June 2008 its price had surged by 142% for an annual 27.4% return.

The investor who ignored the news and bought oil would have turned every thousand dollars of his investment into nearly $2,500 in five short years.

These stories are anecdotal, but the issue of the press giving the wrong coverage and creating noise for investors has been studied more rigorously. Three finance professors at the University of Richmond found that “positive stories generally indicate the end of superior performance and negative news generally indicates the end of poor performance.”

Ignoring noise is difficult, because it generally means going after the investments not in the news.

With that in mind, let´s find a more contemporary example.

Although the death of nuclear energy hasn´t made the covers of Business Week or the Economist (yet, at least), it has all the cultural and social signs of its demise. After the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan, the Fukushima nuclear disaster brough forth pledges from around the world to divest from nuclear power.

The Italian government passed a referendum in June 2011 cancelling plans for new reactors, with over 94% of voters backing the moratorium.

Germany has been decommissioning nuclear power reactors for the past decade, and only six remain in operation today. These are planned to be permanently phased out by 2022.

In countries with existing nuclear programs, only the United States and the United Kingdom were less opposed to nuclear energy after Fukushima.

Climate change protestors have made the end of nuclear energy a common policy stance. The end of nuclear might not be making magazine headlines, but climate change protestors sure are.

Troubling for the protestors is that in terms of CO2 emissions, nuclear is currently about 10% cleaner than wind power, half as polluting as hydro, and has roughly a quarter the environmental impact as solar electricity production. Depending on what type of production one looks at, nuclear is half the cost of wind and one-fifth that of solar power. Plus it doesn´t expose its users to inconvenient blackouts when the wind doesn´t blow and the clouds block the sun.

Of course, rather than trying to discern the future of uranium by listening to pundits, we can just let the market do the talking.

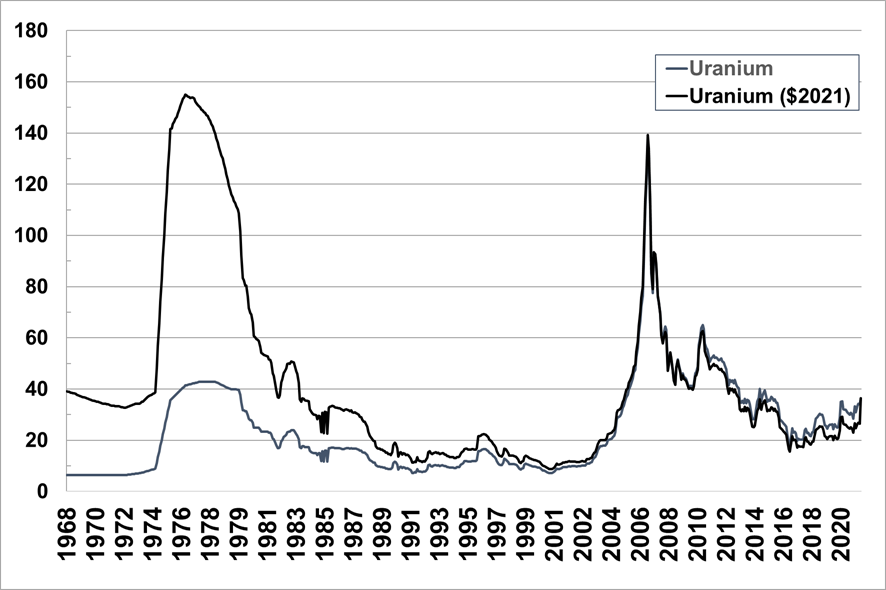

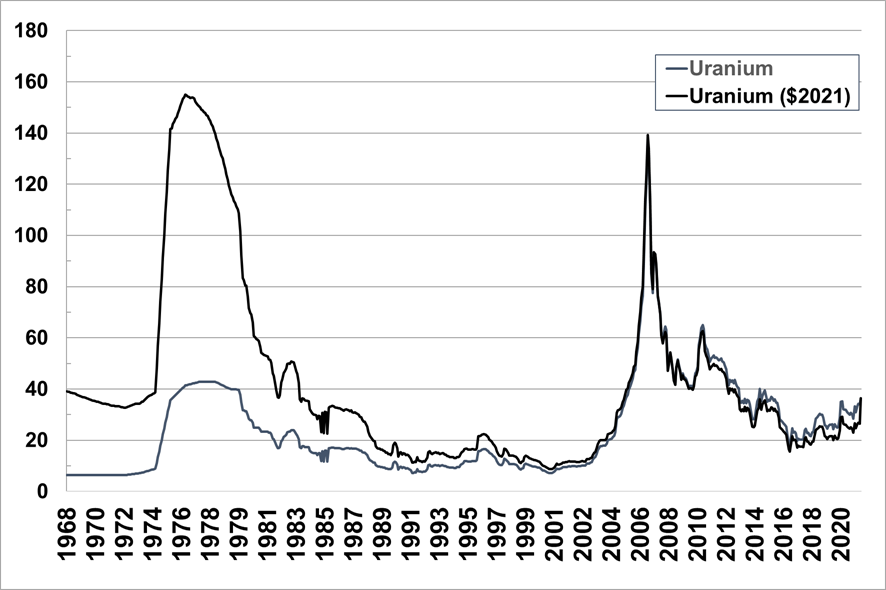

Uranium peaked in May 2007 at $136 before declining 87% to its November 2016 low. Since that month´s price of $18 the metal has been slowly advancing, though still remains well below its highs. In fact, in inflation-adjusted terms it is still priced more cheaply than at any time since the early 2000s.

With its price still at multi-decade lows, energy producers are starting to have a change of heart. After shuttering all its nuclear reactors in 2013, Japan just this month restarted one reactor. Despite a flurry of protests at this reopening, the country sorely needs the extra power. Energy prices in Japan have increased by 30% over the past decade, and nuclear is the natural clean, low-cost option to meet the country´s needs.

Uranium is most commonly traded in its unenriched form, yellowcake, named after its bright color. When it comes to metals, gold may attract the attention of most investors. But as uranium´s price data show, all that glitters might not be just gold.